back

Thomas Leland;-

|

Edgar Allan Poe's rare

|

Tredgold on the Steam Engine.

|

British Fresh-Water Fishes;-

|

A COPY OF

|

The Most Ancient and Famous History

|

Conradi Gesneri Tigurini Medici & Philosophy;

|

Joseph Edmondson;-

|

Wenman, Thomas

|

Vertot, Rene Aubert de

|

Sarrazin, General [Jean. 1770 - 1848]

|

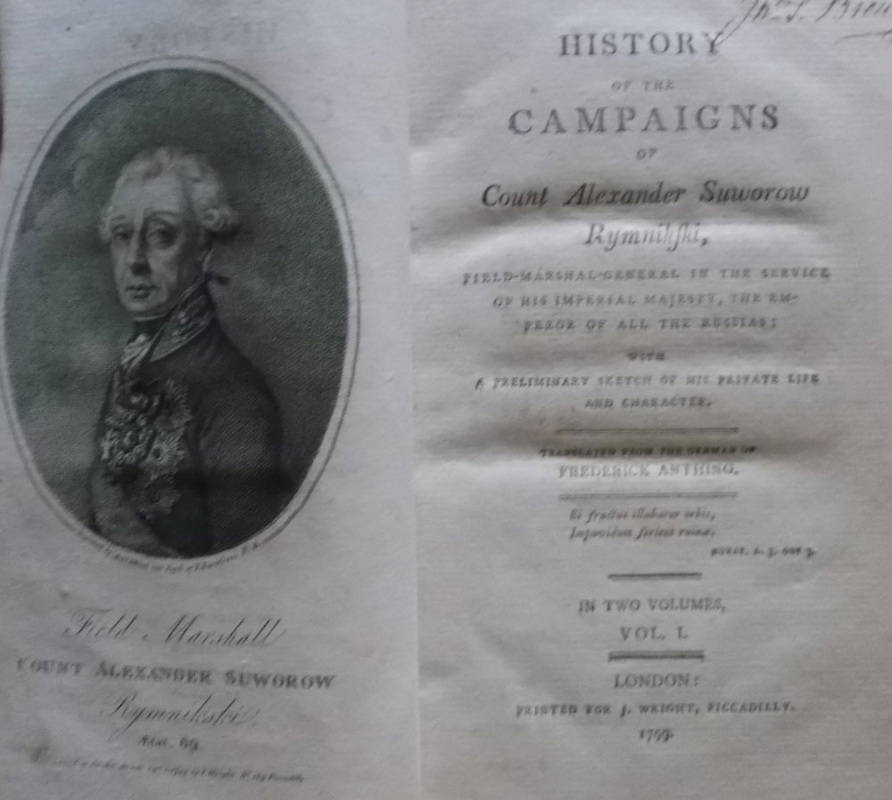

Anthing, Johann Friedrich

|

SHELLEY Percy Bysshe

|

SHELLEY (Percy Bysshe)

|

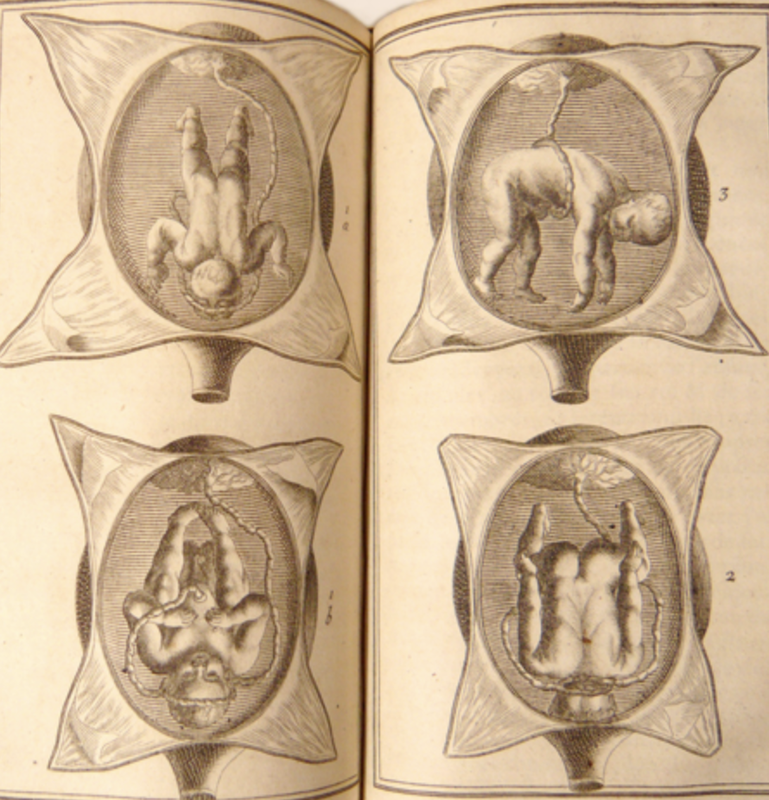

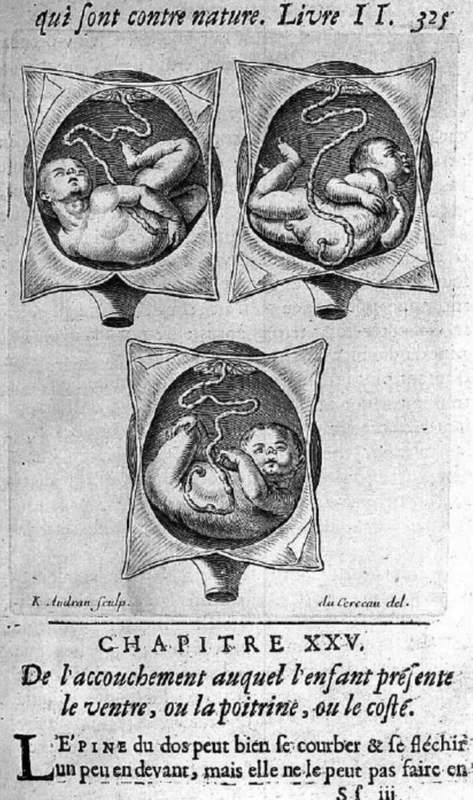

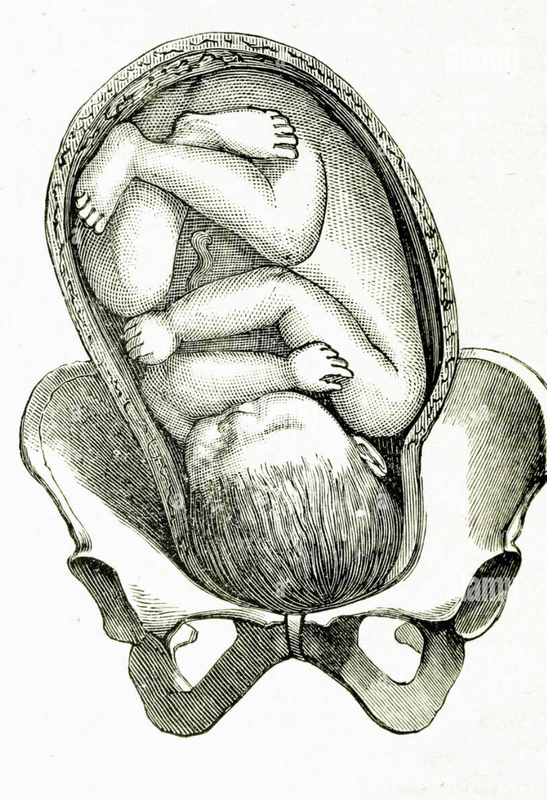

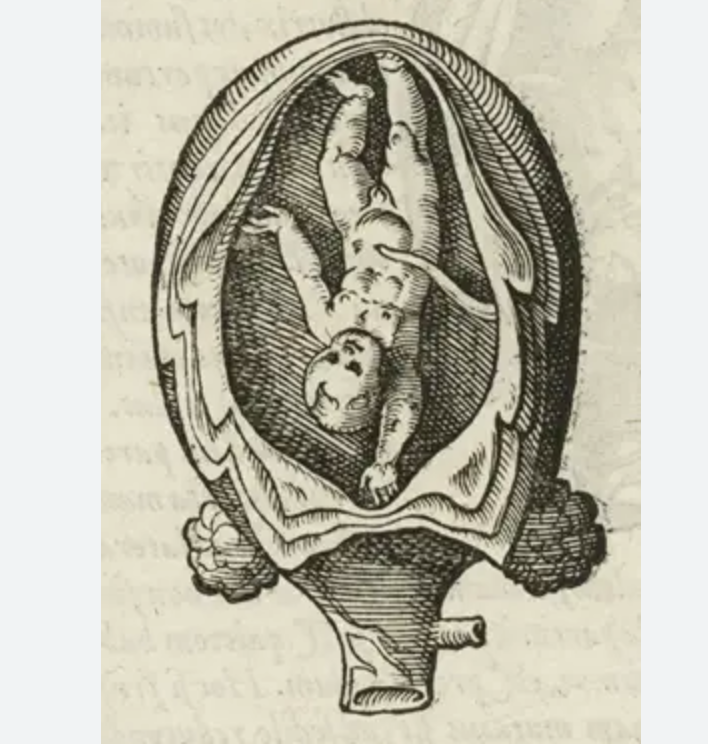

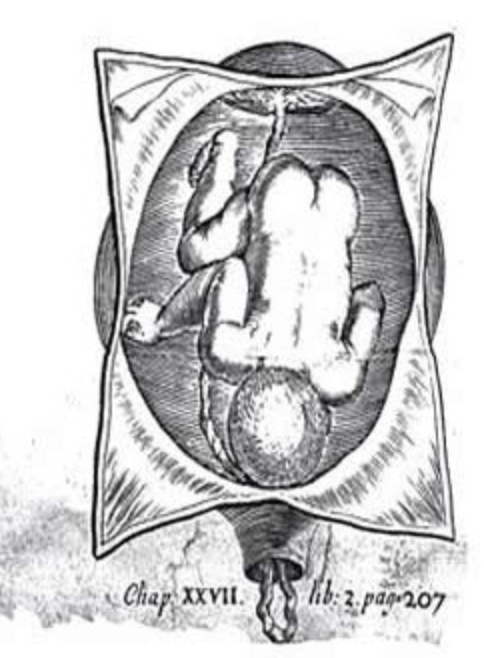

La Pratique des Accouchements 1694

La pratique des accouchemens, par Mr. Peu, maître chirurgien...

The Practice of Childbirth

by

Mr. Peu, Master Surgeon...

$2,500 Buy Now

Published in Paris, by an Boudot-1694, in 8°, of 12ff. 613pp., ill. of 8 engraved plates h.t., - preceded by: Response to the warning of Mr. Mauriceau (15pp.) - and by: Response of Mr. Peu to the particular observations of Mr. Mauriceau on the pregnancy and childbirth of women. (1&4p. and 1 f.), pl. period brown calf, decorated spine, fine copy.

First and unique edition of this very rare treatise, one of the best of the time. Ph. Few having criticised the headshot of Mauriceau, this one attacked him violently in his works, attacks to which the first replied to his advantage twice. The two answers appear here at the head of the copy..Mr. Peu had a very extensive practice in the art of childbirth...his work deserves to be counted among the best of the time... - Not in Osler.

Philippe Peu, (1623–1707) Master Surgeon, man-midwife Philippe Peu explained how to recognise the parts of an unborn child exclusively by touch. Other blame narratives similarly separate adroit from harmful surgeons.

In La pratique des accouchemens (The Practice of Childbirth), an obstetrical treatise published in 1694, the chirurgien accoucheur Philippe Peu outlined a story featuring his active participation in the birthing room:

In the presence of Monsieur l'Evêque my confrere, of Monsieur his son-in-law, and of Madame Ardon midwife, who were charitable enough to assist me, I attended and delivered of her first child the wife of an old clothes merchant named Bérnard living on the rue de la grande Friperie. She had been convulsing for about 24 hours when I left to go there. Her child was dead and half rotten. I removed it with the instrument (i.e. the crochet). She soon recovered perfect health and took better care of herself for the future. Did I mention that she had been abandoned by a man who had made a name for himself and by several of his disciples, who had employed many specious pretexts to win over the mind of the mother, and to prevent me from saving the life of her daughter, crying out against my method, and striving by their vain discourses to save their reputation at the expense of mine.

Carefully naming reliable witnesses who could support his claims, Peu portrayed himself as a beleaguered saviour at odds with a group of self-interested practitioners. Though these rivals are not identified, it is possible some readers would have recognised the men in question. After all, Mauriceau's description of the woman mutilated in 1675 portrays surgeons talking amongst themselves about tragic cases, attempting to assign fault. When Peu criticised the medical manipulations of an unnamed junior colleague in another section of his obstetrical treatise, the outraged younger surgeon (Monsieur Simon) not only recognised himself, but felt sure others in the small surgical community of Saint-Côme would as well. Peu was certainly known for his public quarrels with fellow surgeons, including the celebrated Mauriceau, possibly the “man who had made a name for himself” in the narrative above. In various pamphlets as well as his later treatise, Mauriceau attacked Peu's use of the crochet, a curved hook used to pull dead infants from the womb. He claimed Peu had committed “horrible murders” with the instrument by mistakenly using it on living unborn children. Peu strenuously defended his technique, while criticising Mauriceau's own use of the tire-tête, an instrument designed to remedy cases of impacted head presentation by puncturing the dead child's skull and enabling traction. Peu's story thus continues to defend “his method”, while criticizing those who doubt its efficacy.

Peu's blame narrative furthermore suggests that disputes between chirurgiens accoucheurs took place in the birthing room as well as in print. The lying-in chamber emerges from his tale as a noisy battleground in which men vied for women's patronage, in this case by trying to influence the mother of the suffering woman. Despite implying that the daughter had not taken good care of herself, Peu initially described her condition in a neutral way. He shifted, however, to a more direct and persuasive style to discuss his opponents. The phrase “did I mention” interpellates readers, asking them to take sides in the debate. His strategy alludes to the competitive nature of the medical world in early modern France, when surgeon men-midwives had to defend their reputations continually, even from attacks by fellow surgeons. The unsettled status of male midwives emerges from Peu's tale; the men are not portrayed as a unified group poised to eject female midwives from the birthing room. In fact, Peu aligned himself with a respected female midwife, Madame Ardon, to bolster his claims of superior surgical skill.

La pratique des accouchemens, par Mr. Peu, maître chirurgien...

The Practice of Childbirth

by

Mr. Peu, Master Surgeon...

$2,500 Buy Now

Published in Paris, by an Boudot-1694, in 8°, of 12ff. 613pp., ill. of 8 engraved plates h.t., - preceded by: Response to the warning of Mr. Mauriceau (15pp.) - and by: Response of Mr. Peu to the particular observations of Mr. Mauriceau on the pregnancy and childbirth of women. (1&4p. and 1 f.), pl. period brown calf, decorated spine, fine copy.

First and unique edition of this very rare treatise, one of the best of the time. Ph. Few having criticised the headshot of Mauriceau, this one attacked him violently in his works, attacks to which the first replied to his advantage twice. The two answers appear here at the head of the copy..Mr. Peu had a very extensive practice in the art of childbirth...his work deserves to be counted among the best of the time... - Not in Osler.

Philippe Peu, (1623–1707) Master Surgeon, man-midwife Philippe Peu explained how to recognise the parts of an unborn child exclusively by touch. Other blame narratives similarly separate adroit from harmful surgeons.

In La pratique des accouchemens (The Practice of Childbirth), an obstetrical treatise published in 1694, the chirurgien accoucheur Philippe Peu outlined a story featuring his active participation in the birthing room:

In the presence of Monsieur l'Evêque my confrere, of Monsieur his son-in-law, and of Madame Ardon midwife, who were charitable enough to assist me, I attended and delivered of her first child the wife of an old clothes merchant named Bérnard living on the rue de la grande Friperie. She had been convulsing for about 24 hours when I left to go there. Her child was dead and half rotten. I removed it with the instrument (i.e. the crochet). She soon recovered perfect health and took better care of herself for the future. Did I mention that she had been abandoned by a man who had made a name for himself and by several of his disciples, who had employed many specious pretexts to win over the mind of the mother, and to prevent me from saving the life of her daughter, crying out against my method, and striving by their vain discourses to save their reputation at the expense of mine.

Carefully naming reliable witnesses who could support his claims, Peu portrayed himself as a beleaguered saviour at odds with a group of self-interested practitioners. Though these rivals are not identified, it is possible some readers would have recognised the men in question. After all, Mauriceau's description of the woman mutilated in 1675 portrays surgeons talking amongst themselves about tragic cases, attempting to assign fault. When Peu criticised the medical manipulations of an unnamed junior colleague in another section of his obstetrical treatise, the outraged younger surgeon (Monsieur Simon) not only recognised himself, but felt sure others in the small surgical community of Saint-Côme would as well. Peu was certainly known for his public quarrels with fellow surgeons, including the celebrated Mauriceau, possibly the “man who had made a name for himself” in the narrative above. In various pamphlets as well as his later treatise, Mauriceau attacked Peu's use of the crochet, a curved hook used to pull dead infants from the womb. He claimed Peu had committed “horrible murders” with the instrument by mistakenly using it on living unborn children. Peu strenuously defended his technique, while criticising Mauriceau's own use of the tire-tête, an instrument designed to remedy cases of impacted head presentation by puncturing the dead child's skull and enabling traction. Peu's story thus continues to defend “his method”, while criticizing those who doubt its efficacy.

Peu's blame narrative furthermore suggests that disputes between chirurgiens accoucheurs took place in the birthing room as well as in print. The lying-in chamber emerges from his tale as a noisy battleground in which men vied for women's patronage, in this case by trying to influence the mother of the suffering woman. Despite implying that the daughter had not taken good care of herself, Peu initially described her condition in a neutral way. He shifted, however, to a more direct and persuasive style to discuss his opponents. The phrase “did I mention” interpellates readers, asking them to take sides in the debate. His strategy alludes to the competitive nature of the medical world in early modern France, when surgeon men-midwives had to defend their reputations continually, even from attacks by fellow surgeons. The unsettled status of male midwives emerges from Peu's tale; the men are not portrayed as a unified group poised to eject female midwives from the birthing room. In fact, Peu aligned himself with a respected female midwife, Madame Ardon, to bolster his claims of superior surgical skill.